Introduction

In the past few years, images of women breastfeeding their children have gained a good deal of attention from the media, both negative and positive. In May, 2012 the circulation of images of two female members of the Unites Stated Air Force breastfeeding their children while in uniform caused a great deal of controversy. The images had been created to promote a breastfeeding support group within the local military community, but the images went viral. Many articles and blogs shared the images and accompanied the with contemplation, in some cases, and strongly expressed opinions, in other cases, about whether the images sent a positive message about the nature of motherhood or whether they were inappropriate and undermined the efforts of women to fit in with their male colleagues. In 2014 a pro-breastfeeding campaign sponsored by the Mexico City government and featuring female Mexican celebrities went viral. The campaign encouraged women to breastfed and implied that not doing so was to turn their backs on their children. The campaign was widely regarded as evidence of the sexualization of the maternal body and an institutional failure to understand the constraints and obstacles that inhibit mothers who wish to breastfeed. By contrast, another 2014 breastfeeding campaign featuring college-aged breastfeeding mothers breastfeeding awkwardly in stalls of public restrooms received a good deal of positive reaction. While all three campaigns attempted to raise some awareness of breastfeeding, they did so in different ways by presenting mothers differently within their physical and social environments. Each campaign constructs motherhood differently, and they attribute to mothers varying levels of maternal agency. Previous analyses of breastfeeding campaigns have claimed that such campaigns often serve to marginalize breastfeeding mothers rather than empower them (Hausman, 2007; Kukla, 2006). Others, such as Brett Lunceford (2012), view pro-breastfeeding featuring mothers breastfeeding their children as imagery as harmful rather beneficial to normalize breastfeeding. The aim of this project is to examine the way in which the contexts of both production and distribution, the construction of maternal agency, and the responses to the campaigns operate to create meaning. An additional aim of the project is to explore what the construction of the images and the received meanings reveal and conceal about present attitudes toward breastfeeding and embodied motherhood. By performing a visual rhetorical analysis of breastfeeding advocacy campaigns produced within these differing contexts–a peer-to-peer support group within a military community, a college campus, and a city health initiative–this research project will attempt to determine whether visual advocacy campaigns normalize breastfeeding through the examination of the production context, the construction of maternal agency within the images, and the distribution contexts.

Breastfeeding Advocacy

In Naked Politics: Nudity, Political Action, and the Rhetoric of the Body (2012), Brett Lunceford explores the body as a site of political action. In the third chapter, entitled “Weaponizing the Breast: Lactivism and Public Breastfeeding,” Lunceford argues that lactivism, which uses breastfeeding as a method of advocating for more widespread acceptance and normalization of breastfeeding, poses a challenge to the sexualization of the breast and makes an argument that breasts should be regarded for their functionality. Lactivism challenges the widespread conceptualization of the breast as a sexual object by emphasizing the functionality of the breast and using breastfeeding visibly in public places as a way to normalize breastfeeding. Lunceford perceived there to be a significant difference between lactivism that takes place on location in the public and lactivism through still images. He claims that “There is a function to public breastfeeding that is readily apparent—the child needs to be fed at that time and no amount of reasoning with the infant will stop the child’s insistent crying. At the moment when the photograph is posted, however, the urgency has passed” (Lunceford, 2012, p. 66). He claims that the staging of public nursing is counterproductive because it makes breastfeeding a spectacle, and because there is no urgency or immediate need to capture an image of a breastfeeding mother and child pair, advocacy through imagery is even more of a spectacle than a staged nurse-in. This, he claims, serves to “undermine their message that breastfeeding should be considered natural and unspectacular” (Lunceford, 2012, p. 67).

In Rhetorics of Display, Lawrence J. Prelli claims that our very reality (or realities) or “much of what appears or looks to us as reality is constituted rhetorically through multiple displays that surround us, compete for our attention, and make claims” (2006, p. 1). Display, he claims, is the primary form of rhetoric in contemporary western society (Prelli, 2006, p. 2). Displays play such a significant role in society because “the meanings they manifest before situated audiences result from selective processes and, thus, constitute partial perspectives with political, social, or cultural implications” (Prelli, 2006, p. 11). To examine displays, Prelli claims, we can analyze rhetorics of display by examining how they reveal partial perspectives by concealing other perspectives.

Prelli’s theory of displays as simultaneously revealing perspectives and concealing perspectives is reminiscent of Kenneth Burke’s concept of “terministic screens.” In A Grammar of Motives (1969), Burke says that, “Men seek for vocabularies that will be faithful reflections of reality. To this end, they must develop vocabularies that are selections of reality. And any selections of reality must, in certain circumstances, function as a deflection of reality. Insofar as the vocabulary meets the needs of reflection, we can say that it has the necessary scope. It its selectivity, it is a reduction” (1969, p. 59). Burke seems to be arguing that choices of vocabulary are a selection of particular perspectives of reality, and as they reflect particular perspectives of reality, they also function to deflect other perspectives of reality.

In his choice to name visual depictions of breastfeeding in attempts to advocate a wider acceptance of breastfeeding in public places, Lunceford is applying a terministic screen that views breastfeeding as something that should be protected from public view when and if possible. His argument suggests that efforts to challenge dominant notions about womanhood and motherhood have to be functional, else the existence of these images or displays serves no useful function. Lunceford’s view seems to coincide with what Bernice Hausman refers to as the androcentric view of breastfeeding. Hausman’s “Things (Not) to Do with Breasts in Public: Maternal Embodiment and the Biocultural Politics of Infant Feeding” (2007) is concerned with the way in which maternal embodiment of breastfeeding is deemphasized. Hausman carries out a biocultural analysis of representations of breastfeeding (representations that aim to present, promote, or analyze breastfeeding) to examine the social conflicts surrounding breastfeeding. She explains that most depictions of breastfeeding, even in materials meant to promote breastfeeding, attempt to suppress the embodied nature of the breastfeeding experiences and use technology (such as the pump) to mediate social anxiety surrounding public breastfeeding (Hausman, 2007, p. 481). She says, “Indeed, not being able to visualize or represent breastfeeding is related to a need to establish and maintain control over mothers, imagined themselves as irresponsible and unreliable, by managing their relation to their infants through technology” (Hausman, 2007, p. 481). Lunceford’s claim that images of breastfeeding undermine attempts to normalize it by drawing attention to it can be viewed as an attempt to control the spaces and places that breastfeeding can be perceived of as normal. The argument that breastfeeding is only an acceptable sight if it is seen in real-time and the site is unavoidable because of the infant’s need for nutrition actually seems an effort to reinforce breastfeeding as abnormal. Lunceford seems to adhere to the androcentric view that “mothers are persons on the condition that they act like male persons” (Hausman, 2007, p. 494); unless, of course, it is unavoidable for them to do so because the baby has a need to be fed. In “Breast is Best…But Not Everywhere: Ambivalent Sexism and Attitudes toward Private and Public Breastfeeding,” Michele Acker claims that those who feel that women’s bodies should be shield from view if possible are viewing women and their bodies through the lens of “benevolent sexism” (Acker, 2009, p. 479). Those benevolent sexists “believe in cherishing and protecting women, idealizing traditional women” (Acker, 2009, p. 479). Perhaps Lunceford’s argument that breastfeeding and representing breastfeeding in public spaces, particularly when there is no immediate need for mothers to be seen doing so, is based in part on a benevolent sexist attitude.

Rebecca Kukla’s “Ethics and Ideology in Breastfeeding Advocacy Campaigns” (2006) examines the way in which breastfeeding campaigns have inadvertently conveyed messages about breastfeeding that reveal perceptions of the nursing mother, the breast, and the appropriateness, or not, of the public breastfeeding. Utilizing social semiotics, Kukla conducted a visual rhetorical analysis of several American breastfeeding campaigns that attempt to intervene into the infant-feeding choices and behaviors of mothers. Modern health care, according to Kukla, views the mother as having the primary responsibility for the health of her child. Kukla points of that breastfeeding campaigns often present breastfeeding, which scientific studies have suggested is the healthiest method of infant-feeding, as a civic duty, an ethical practice, and a practical method of feeding. Before beginning the analysis of the images, Kukla reviews the rhetorical exigency for breastfeeding campaigns. Breastfeeding is widely viewed as the best method of breastfeeding for a number of reasons; however, breastfeeding rates in the United States fall below target rates. She explains that breastfeeding advocates were confused about why mothers choose not to breastfeed despite the fact that it is well known that breastfeeding is very beneficial and a pleasant experience. Breastfeeding advocates assumed that the reason that mothers were not breastfeeding was because they were not getting the message. Rather than examining the reasons that mothers were not breastfeeding, in 2004 the Department of Health and Human Services decided to hire the private advertising agency the Ad Council to design a slogan and breastfeeding promotional materials. By examining the advocacy campaign through the lens of semiotics and analysis of the ethics of the campaign, Kukla examines what the campaign reveals about the culturally situated nature of breastfeeding. Kukla explores the cultural factors that make breastfeeding difficult: sexualization of the breast, codes dictating appropriate public and private behaviors, barriers for working mothers. Kukla points out that many images of women breastfeeding show women wearing nightgowns or robes, suggesting that breastfeeding is a domestic act. The narrative about breastfeeding suggests that it is easy and joyful. Women who have difficulties with breastfeeding are seen as “deviant and unmotherly” (Kukla, 2006. p. 169). Mothers who have difficulty feel “unmotherly, shameful, incapable, defective, and morally inadequate” (Kukla, 2006, p. 170). Rather than helping mothers overcome these barriers, the DHHS campaign reinforces the notion that breastfeeding is private by including pictures of objects meant to represent breasts (ie. an ice cream sundae with two scopes each topped with a cherry). The text accompanying the images reminds mothers why choosing not to breastfeed may harm children, which was a change from past advocacy campaigns that promoted the benefits. Kukla argues that this campaign was harmful because it painted mothers who face barriers to breastfeeding as harmful to their children. Kukla claims that the DHHS campaign and similar campaigns are “unethical assaults” and campaigns that focus on risk in this way are normative (2006, p. 175).

Both Hausman and Kukla had found that many attempts at breastfeeding advocacy had actually served to marginalize breastfeeding mothers through their choices of visual imagery of pro-breastfeeding materials. Their examinations of these materials reveal that pro-breastfeeding campaigns often present an androcentric view of breastfeeding. Lunceford’s claim that pro-breastfeeding imagery depicting mothers nursing their children undermines attempts to normalize breastfeeding. While it certainly seems possible for breastfeeding campaigns to present a successful visual argument for breastfeeding that reveals rather than conceals the societal and material constraints placed on breastfeeding mother-child and does not undermine attempts to normalize breastfeeding, scholarship on breastfeeding advocacy campaigns has not yet compared unsuccessful attempts to normalize breastfeeding through visual advocacy to those visual campaigns that do seem to do so successfully. In order to make these comparisons, this research project will rely on social semiotics to explore the three campaigns in attempt to address the following questions:

- How does the construction of these campaigns reveal and conceal perspectives on the nature of the female body, the nature of breastfeeding, the mother-child relationship, and the place of breastfeeding in society?

- How have responses to these campaigns reveal/conceal perspectives on the nature of the female body, the nature of breastfeeding, the mother-child relationship, and the place of breastfeeding in society?

- Have these campaigns reinforced or challenged the problems with campaigns Kukla analyzed in 2006? (The sexualization of the breast, codes dictating appropriate public and private behaviors, barriers for working mothers, and the image of breastfeeding as domestic and joyful?)

Objects of Study

The three pro-breastfeeding campaigns that were chosen for this analysis were chosen because the approached their audiences and arguments in varying ways. They all differed in the way in which they construct motherhood. Each campaign took a different approach in the effort to normalize breastfeeding, and each campaign was aimed at a different segment of society.

Campaign #1: Mom2Mom Campaign

The first object of study is a set of images of two female members of the Air National Guard members who are nursing their children in what seems to be a public park. The images themselves are professional photographs that were taken as part of a larger project in which women who were part of the Mom2Mom Breastfeeding Support Group at Fairchild Air Force base were photographed nursing their children. Though the images were intended to be used for materials to be distributed locally to support the group, the images went viral in late May 2012 and were posted on many news websites and blogs. Some reactions were positive, while other reactions are negative. The choice to have the subjects pose in their uniforms seemed to be made to convey a message about the dual nature of military motherhood.

Campaign #2: Mexico City Campaign

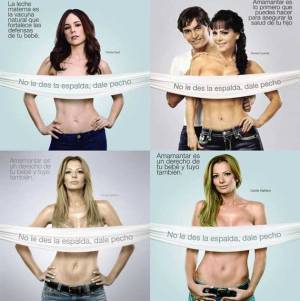

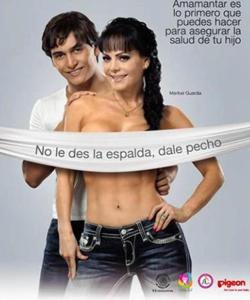

The second set of images came from a pro-breastfeeding campaign sponsored by the government of Mexico City. The images were meant to be distributed throughout the city. They were aimed at convincing mothers that they should breastfeed their children, and that failure to do so was in essence turning their backs on their children and risking their children’s health. The images were distributed on a number of news websites in the United States, and reactions seem to have been primarily negative.

Campaign #3: When Nature Calls Campaign

The third set of images are from a breastfeeding advocacy campaign produced as a class project by Kris Haro and Johnathan Wenske, students as University of North Texas. The campaign features images of three college-age mothers breastfeeding their babies while sitting on toilets in public restrooms. The goal of the campaign was to shed light on the societal constraints that breastfeeding mothers face. The image went viral on a number of media outlets. Reactions to the images were primarily positive.

Analytic Approach and Methodology

To examine these three campaigns and address the research questions, this project relies on a three pronged approach to analysis. The philosophical lens that guides the analysis of the image is social constructivism. In order to discover how meaning is made in and with these images, this project will rely on David Weintraub’s (2009) framework of discourse analysis of visual images. This approach calls for an analysis of the image and the text, an analysis of the production and distribution contexts of these images, and the way in which the image and texts work together within the social context to create a version of reality. To understand how these campaigns construct reality in the social context, this project relies on Prelli’s theory of the rhetoric of displays as a way of exploring what is revealed and concealed in the images.

Philosophical Assumptions and Theoretical Lenses

This project is grounded in two types of philosophical assumptions (ontological and epistemological) as John Creswell describes them in Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches (2012). One philosophical pillar of this research project (the ontological lens) is the assumption that there can be multiple and competing versions of reality. The ontological and epistemological (what knowledge is and where it comes from) assumptions in this project are informed by social constructivism. Social constructivism, according to Creswell, espouses that individuals develop subjective meanings through their experiences, and that these “meanings are negotiated socially and historically. In other words, they are not simply imprinted on individuals but are formed through interaction with others (hence social construction) and through historical and cultural norms that operate in individual’s lives” (Creswell, 2012, p. 25).

Burke’s concept of terministic screens and Prelli’s theory of displays are useful theoretical lenses that allow for application of social constructivism to the rhetorical analysis of visual images in order to understand the ways in which meaning is made with and from those images. Burke’s concept of terministic screens relies on the idea that when one version of reality is presented through choices regarding representation, another version of reality is deemphasized by omission. Prelli’s theory operates similarly. Displays reveal versions of reality, and because some possible reality is presented, other conceptions of reality are de-emphasized.

Discourse Analysis

The structure of the analysis of these three visual campaigns is based in the discourse analysis framework that David Weintraub described in “Everything You Wanted to Know, but Where Powerless to Ask” (2009). This text provides a discourse analysis framework for the study of images. Discourse analysis is based on the idea of intertextuality; therefore, the meaning conveyed by the combination of the image and the accompanying text is an important element of the analysis of an image in discourse analysis. Context is also very important in discourse analysis. Weintraub says that the meaning of images “resides not solely within themselves, but also within the context of how and why the images were produced and distributed” (Weintraub, 2009, p. 200). According to Weintraub, discourse analysis involves three core moves: describing the content of the image and the text, analyzing the context of the production and distribution of the image and the text, and explaining how the image and text work together to construct a version of reality (2009, p. 206). In the article, Weintraub provides a detailed description of the process of conducting discourse analysis. To describe content, one should examine the subjects, composition, camera position and angle, tonality and color, look and gesture, size relationships, headlines, captions, articles. To analyze the context, the researcher should analyze the production context, the distribution context, and the reception contexts. To analyze the construction, or the reality, the researcher needs to look at the public image of the subject, myths, and ideas and concepts that are prompted by the image (Weintraub, 2009, p. 210-214). To accomplish the analysis of the images and texts, this project relies in social semiotics of the visual as described by Jewitt and Oyama (2001). The approach to the analysis of the distribution and reception of the images are informed by Gillian Rose’s Visual Methodologies (2012) and Groarke and David S. Birdsell’s “Toward a Theory of Visual Argument” (1996).

Social Semiotic Approach to Visual Analysis

In “Visual Meaning: A Social Semiotic Approach,” (2001) authors Carey Jewitt and Rumiko Oyama claim that visuals are meant to carry out three metafunctions: they create representations, they create interactions between speaker/author and listener/reader, and they bring together parts of a representation and interaction to make a whole text (2001, p. 140). It is tempting to view an image as a representation of reality, but as Jewitt and Oyama explain, visual artifacts convey meaning in much more complex ways. According to Jewitt and Oyama, visuals represent meaning through narrative structures in which the visual is telling a story, or they can convey meaning through conceptual structures. The authors explain the elements of visuals that, according to social semiotics, convey meaning. Social semiotics analyzes the way in which visuals create interactive meaning between the image and the viewer through contact, distance, and point of view. It looks at how images convey compositional meaning through information value (placement of elements in a composition), framing, salience, and modality. Social semiotics, as Jewitt and Oyama describe it, is useful for analyzing the visual image itself. While it does not tell us retroactively what the audience feels about the visual, social semiotics is useful for gauging the ways in which the image may appeal to the research proposal project. Jewitt and Oyama’s explanation of the difference between a conceptual image and a narrative image is useful to this project because the campaign that are being analyzed are best understood as having a symbolic or analytic structure because in the symbolic structure the identity of a participant is defined by the presence, or the absence in the case of the Mexico City image, of another person in the picture (baby). The analytical structure would view the mother and child as two parts in one whole.

Analyzing Production and Distribution Contexts

Gillian Rose’s Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials (2012), which draws from a number of theories and methodologies of the visual culture theory, suggests that there are actually three sites for the production of meaning of images: the site of the production of the image, the image itself, and those sites where it is encountered by audiences (Rose, 2012, p. 19). She also claims that each of the three sites has three modalities: technological, compositional, and social, and that differing theories of visual interpretation have as their foundations differing views of which of sites and modalities are most important (Rose, 2012, p. 40). Like many others scholars discussing the use of methodologies, Rose emphasizes using the methodology that is most appropriate for addressing the research question based on the sites and modalities that are being examined in the project (2012, p. 40). She explains five possible ways of examining visual artifacts in a visual analysis project: examinations of the way images visualize social difference, how images are looked at, the embeddedness of images in culture, the ways in which the audience bring their own interpretations to images, and the agency of images themselves.

Like Rose, Leo Groarke and David S. Birdsell’s “Toward a Theory of Visual Argument” (1996)is focused on locations of interpretation; however, the refer to these sites as “contexts” rather than “sites.” They are concerned primarily with the visual context of the image, the verbal context of the image, and the cultural context of the images (Birdsell and Groarke, 1996, p. 316), all of which seem to fall under the umbrella of the site of interpretation, one of the three sites of interpretation of a visual image that Rose describes in Visual Methodologies. Groarke and Birdsell approach visual analysis from the field of rhetorical studies. They claim that visual analysis should analyze the visual image itself, look at the contexts of the image, examine the consistency of the interpretation of that visual, and record changes in the perspective of the image over time. Groarke and Birdsell suggest a method that encompasses more than simply an analysis of the way in which the image itself produces meaning. Their approach involves the study of several sites of production of meaning and can incorporate the study of differing modalities.

The idea that the immediate visual context must be accounted for in an analysis of a visual is very important to the analysis of these breastfeeding campaigns. In the images of these campaigns, even the “ambient environment” within the image itself and which the images are contained seemed to make a difference in the interpretation of the images. The Mexico City campaign moves women from any context, the Mom2Mom group places the women outside in an open environment, the campaign entitled “When Nature Calls” places the nursing pair in a dimly light restroom stall.

Heuristic for Visual Analysis

To facilitate the three levels of analysis of the images in this project, the visual analysis, the cultural analysis, and the rhetorical analysis, a heuristic was created. The first section of the heuristic contains a visual analysis section that relies social semiotics, as described in Jewitt an Oyama’s “Visual Meaning: A Social Semiotic Approach” to analyze how visuals create meaning in the interaction between the image and the viewer through contact, distance, and point of view. It looks at how images convey compositional meaning through information value (placement of elements in a composition), framing, salience, and modality. The second part of the heuristic analyzes the cultural context in order to explore the production and distribution contexts of the images and the way in which meaning is made from the images through those contexts. The final portion of the heuristic relies in the previous two analyses to examine the rhetoric of the messages and to look closely at what the images reveal and conceal about the subjects of the images, what the images reveal and conceal about the context of the image’s subjects, and what the reception of images reveals about societal attitudes toward embodied motherhood and breastfeeding. For the purposes of this in depth analysis, one representative image was chosen from each of the three campaigns. There are many commonalities between the images that make up each of the campaigns and only a few differences. Each campaign contained images based on very similar compositional elements; therefore, conclusions about the three campaigns based on in-depth analysis can be generally applied to the overall message of the campaign.

Results of Analysis

Campaign#1: Mom2Mom Campaign (Follow Link for Completed Heuristic)

The image from the Mom2Mom breastfeeding group campaign shows two mothers in Air Force National Guard uniforms breastfeeding their children. The images were created for the purpose of promoting Mom2Mom breastfeeding support group at Fairchild Air Force Base. The photographs were taken as part of a larger photoshoot including a number of other women who were involved in the group, and the group’s founder and one of the mothers in the image, has claimed that the mothers were given permission to pose for the images. The images were distributed on the photographer’s website and was going to be placed on posters and other materials created as promotional materials. They are sitting outside in what seems to be a park while breastfeeding their children. One of the mothers is breastfeeding twins who are sitting up in her lap. She is smiling while looking at the camera. Lunceford might claim that this mother’s acknowledgement that she is posing for the camera makes the image a spectacle and undermines the normative effort of the campaign. The other mother is nursing female child who is laying across her lap. This mother is looking down into the face of her child. The choice to have these mothers pose in uniform seems to suggest that women in uniform may need a particular kind of support and that they may also be more convinced to attend a group meeting if there are women like them in the group.

The military uniform seems to suggest strength and a warrior ethos. At the same time, the image has a soft, maternal element. The image attempts to convey a message that military mothers occupy dual roles and that they do it with strength and confidence. The mothers seem to be comfortable with the level of agency that they have within their immediate environment and perhaps their social context as well. The choice to breastfeed in uniform for visual image campaign cannot be taken likely, and shows that the mothers are comfortable with doing so.

After the photographs of the women were made public, the images of the women in uniform received a great deal of attention in the media, on social networking sites, on blogs, and in discussion threads, especially those focused around the topics of either breastfeeding or the military. One headline from The Air Force Times posed the question “Is This OK—Or Unprofessional?”

Some who wrote about the images applauded the mothers for navigating their dual roles successfully and showing the strength of motherhood. Other responses, including some from other women who serve in the military, suggested that women in uniform should not be seen nursing in public because this undermines the efforts of women in the military to be seen as equal to men. For them, seeing women in uniform nursing will cause their male counterparts to view them differently. It was not until approximately seven months later, in January of 2013, that the ban on women in combat roles was lifted. Those who wanted to see women allowed in combat may have had reservations about the display of maternal embodiment.

Terran McCabe, one of the mothers photographed nursing her children in uniform, claims that they were given permission to participate in the photo-shoot by superiors. The hope of those involved in the project was that the images would be encouraging to other women and that the images would be placed in clinical exam rooms (McCabe). According to McCabe, Air National Guard officials changed their minds about the photographs after the images gained attention, and they asked McCabe to refrain from speaking about the images and to remove the images from her Facebook profile. Acker might argue that this is evidence of a benevolent sexism, though the National Guard’s official position was that it is not acceptable to be photographed in uniform in support of an organization or campaign and their position was not because of the breastfeeding itself.

Those who read these images as spectacle, as Lunceford would, and claim that the images undermine attempts to normalize breastfeeding are also suggesting that there is an appropriate way for mothers to behave will breastfeeding. For those who take issue with where the mothers are looking suggests that that there should only be a focus on the baby and not the external world. This view of the image constructs breastfeeding as private and perhaps even an otherworldly experience that is in need of protection, and that breastfeeding mother-child couples cannot or should not have full interaction with the wider world.

The image conceals the obstacles that breastfeeding mothers in uniform face. The very reactions to the image make these obstacles evident. The lack of places to pump, long hours at work, and potential separation from their children is not addressed. Instead, the mothers seem to present a confident and happy maternal ethos despite the fact that they work within a masculine environment. This expression of happiness and fulfillment seemed to cause cognitive dissonance for those who view breastfeeding as appropriately and necessarily private and as military bodies as occupying appropriately masculine places.

Campaign #2: Mexico City Campaign (Follow Link for Completed Heuristic)

The second image is part of a “prolactina” campaign in Mexico City. It was meant to encourage women to breastfeed their children, and this particular image, one of a popular actress and singer with her adult son, makes an argument that the benefits of breastfeeding will last until adulthood. Maribel Guardia is accompanied by her approximately 20 year old son, Julián Figuero. Guardia is topless, and there is a banner covering her large breasts. The banner says, “No le des la espalda, dale pecho.” In essence, it presents this petition to mothers: Don’t turn your back on them, give them your breast.” In the upper right side of the image, the text reads: “amamantar es lo primero que puedes hacer para asegurar la salud de tu hijo.” Translated it reads: “Breastfeeding is the first (best) thing you can do to ensure the health of your child.” Citizens of Mexico would likely know the identity of these subjects, but those with little knowledge of Mexican celebrities who are not well known in the United States, the relationship between the subjects is not clear. The text that accompanies the images helps make the relationship clear.

The target audience was new mothers, and the goal was to encourage women to breastfeed their children for at least the first 3-6 months, but the image presents the maternal body in a very sexual way. Guardia is nude from the waist up, and her body is very toned and fit, particularly for a woman in her fifties. The images was picked up in various blogs and news outlets in Mexico, and then was published in blogs and news websites in English in the United States, including the Huffington Post. Most outlets took a negative view of the campaign. The controversy surrounding the image was focused on the fact that the campaign used famous actresses, most of whom were large breasted and model-thin, and seemed to sexualize motherhood. Various outlets claimed that the image was racist, classist, and sexist. Within a day of the launch of the campaign, one of the actress-models renounced her involvement.

The image of Guardia and her son underscores dominant notions of femininity and sexualizes motherhood, which suggests that the images have been created through an androcentric view if mothers and women. The images in the campaign were referred to as being racist, sexist, and classic because they depict motherhood through the use of wealthy women who are associated with strongly associated with sexuality and masculine desire, and those women are topless with a banner covering their breasts. The campaign is meant to advocate for breastfeeding, but the breasts (other than the curvature at the tops of the breasts and the cleavage) are concealed for the sake of modesty; however, the actress is otherwise exposed from the waist upward. Concealing the breasts while revealing much of the rest of the body conveys the notion that breastfeeding is being associated with sexuality, or at least with highly sexualized bodies. The image seems to underscore androcentric views of maternity and women. The following image is typical of the images that result from Google searches of “Maribel Guardia”:

In addition to sexualizing mothers, the campaign also positions mothers as objects with the function of raising children. The masculine son stands behind his mother with his hands on her shoulder and waist. This suggests possession. This seems to be a visual representation of an androcentric view of motherhood. The son is the actor, the mothers is being acted upon here. It could suggest that mothers have a responsibility to the nation to breastfeed so that they raise strong and healthy children (particularly sons). What would be the affect if the mother was clothed and was embracing her son?

The fact that the campaign focused on a wealthy actress seems a bit tone-deaf because many of the obstacles that prevent women from breastfeeding in Mexico are caused by socioeconomics and lack of support for breastfeeding mothers. The image does not confront the fact that, “A lack of good nutrition, adequate maternity leave and opportunities to pump milk at work keep many Mexican mothers from the practice” (“Mexico City’s Breastfeeding”).

Campaign #3: When Nature Calls Campaign (Follow Link for Completed Heuristic)

The third campaign is a set of images created by University of North Texas students Kris Haro and Johnathan Wenske created as a class project. Haro and Wenske claim that the images were created to support a proposed bill that would legalize breastfeeding in public places anywhere that a mother and her child are authorized to be and prohibits interference with the breastfeeding mother and child. The subject is a college-aged mother sitting on a public toilet nursing her child. The image is cropped so thit is focused in on the constricted space of the restroom stall. The lighting is dim. The mother is looking at the camera, and her expression is wary. She does not seem to be comfortable in the surroundings. Her child is looking up at her mother’s facing and playing with the neckline of her mother’s shirt while she nurses. While it is clearly a posed shot, the mother and child relationship is real, and the expression itself might even be the product of her true feelings about nursing her child on a toilet.

In support of the proposed bill, the image sends a message that mothers often feel they must (or are forced to) breastfeed discretely in undesirable places. The image is arguing that mothers should be allowed to breastfeed elsewhere. At the top of the image is the text “Table for two.” At the bottom of the image there is a banner that contains the phrase “Would you eat here?” There is also an explanation, in fine print, of the fact that breastfeeding in public is not legally protected from harassment or attempts to make them leave public spaces in the state of Texas. It petitions viewers to contact state and local lawmakers to support a proposed law for those protections. The image relies on the widespread understanding of restrooms as unsanitary and germ-riddled. It is not a desirable place to eat for adults, why should it be a place where children eat? Unlike the other two images, the target audience is not mothers themselves. The target audience are citizens of the state of Texas. The intent is to raise awareness of the general public in the state of Texas that breastfeeding should be a protected right. In this case, mothers are not the direct audience, but could be an audience in that they realize that others have had shared experiences and that perhaps changes could be made if awareness was raised. A number of media outlets wrote about the image, and most of these responses were positive and viewed the images a containing a positive message and showing the reality of the marginalized spaces that maternal bodies occupy.

The image shows that nursing mothers occupy a marginalized space in society. While many pro-breastfeeding campaigns target mothers and expectant mothers as their audience, suggesting that they have a moral or ethical imperative to breastfeed their children because of the health benefits, this campaign take on one of the major obstacles that breastfeeding mothers face. Kukla says that many breastfeeding campaigns do not address the obstacles, and this is one campaign that does.

The image reveals not the point of view of an organization petitioning women to breastfeed, nor does it focus on offering breastfeeding mothers support and attempting to convey the message that breastfeeding is easy and can be done. Instead, the image targets the reasons that mothers are in need of support, because the embodied nature of mothering through breastfeeding is largely misunderstood and misrepresented. Discomfort and sexualization of female bodies through benevolent sexism marginalizes breastfeeding mothers. This image shows the results of that sexism. Those who expect breastfeeding mother-child pairs to hide themselves away may not thought of the way in which the mothers are being pushed out of society and asked to retreat to undesirable places to nurse.

What may be concealed in the image is sense of confidence and agency. This mother seems to have little agency, and her agency should be increased. Some who do not understand the benefits of breastfeeding might see this mother’s discomfort as a reason that bottle-feeding might be preferable. Happiness with the mother-child breastfeeding relationship is not clearly evident, and this mother could be viewed who is feeding her child out of a sense of duty and not because she enjoys the embodied nature of mothering through breastfeeding.

Conclusion

An analysis of the Mexico City campaign confirms that some breastfeeding campaigns continue to marginalize mothers, just as past advocacy attempts analyzed by Kukla and Hausman have done. Like the DHHS campaign, the Mexico City campaign makes moral imperative out of breastfeeding while marginalizing mothers. On the other hand, the other two campaigns focus more on sending a message about the position of mothers within society. It seems that there are alternatives to advocacy campaigns that marginalize women and make breastfeeding a moral imperative. Both the “When Nature Calls” and the Mom2Mom campaign challenge androcentric and benevolent sexist codes of acceptable behavior, but the Mom2Mom campaign challenges benevolent sexism and androcentric views of the female body by presenting a direct challenge to resistance to public breastfeeding. The image almost conceals the marginalized position that breastfeeding mothers, especially those in uniform occupy. The reactions to the campaign show that American society is still not comfortable with the embodied nature of mothering through breastfeeding. In contrast, the “When Nature Calls” campaign received a much more positive reaction? Why is it that these images, showing mothers reluctantly adhering to the norms established by benevolent sexism, is the one that received the most positive reactions? Is it that the image shows the real embodied experience of mothers who operated within societal norms rather than challenging them, and in doing so it exposes the problems inherent in these marginalized positions? Nedra Reynolds says that “female knowers adapt to their marginalized position in a male-dominated culture by seeing differently—and learning different things” (1993, p. 330). The “When Nature Calls” campaign focuses on what is seen and experienced within the marginalized position, giving a glimpse into that different way of knowing that is the result of being marginalized. Perhaps the image is so powerful because it focuses not on what society sees, or should see, when they encounter a breastfeeding mother in public, but rather it reveals that which the public does not see when they do not.

Works Cited

Acker, M. (2009). Breast is best… but not everywhere: ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward private and public breastfeeding. Sex roles, 61(7-8), 476-490.

Birdsell, D. S., & Groarke, L. (1996). Toward a Theory of Visual Argument. Argumentation and advocacy, 33, 1.

Blum, L. M. (1993). Mothers, Babies, and Breastfeeding in Late Capitalist America: The Shifting Contexts of Feminist Theory. Feminist Studies, (2). 291.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

Haro, K. & Wenske J. When Nature Calls. Retrieved from http://whennaturecalls.org

Hausman, B. L. (2007). Things (Not) to Do with Breasts in Public: Maternal Embodiment and the Biocultural Politics of Infant Feeding. New Literary History, (3), 479.

Knoll, A. (2104). The Mexican Government Shows How NOT to Promote Breastfeeding. Bitch Magazine. Retrieved from http://bitchmagazine.org/post/the-mexican-government-show-how-not-to-promote-breastfeeding

Kukla, R. (2006). Ethics and ideology in breastfeeding advocacy campaigns. Hypatia, 21(1), 157-180.

Lunceford, B. (2012). Naked politics: Nudity, political action, and the rhetoric of the body. Lexington Books.

McCabe, T. (2013). Terran McCabe: The Air Force Breastfeeding Mom Finally Speaks Out. I Am Not the Babysitter: Confessions of a Transracial Family. Web.

Prelli, L. J. (Ed.). (2006). Rhetorics of display. Univ of South Carolina Press.

Rose, G. (2011). Visual methodologies: An introduction to researching with visual materials. Sage.

Rose, L. M. (2012). Legally public but privately practiced: Segregating the lactating body. Health communication, 27(1), 49-57.

Weintraub, D. (2009). Everything you wanted to know but were powerless to ask. Visual communication research designs, 198-222.